Logic and Language

|

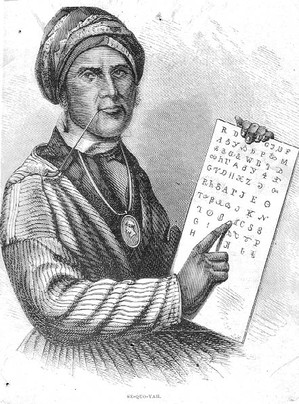

Sequoyah (ᏍᏏᏉᏯ Ssiquoya, as he signed his name, or ᏎᏉᏯ Se-quo-ya, as his name is often spelled today in Cherokee) (ca. 1770–1843). In 1821 he completed his independent creation of a Cherokee syllabary, making reading and writing in Cherokee possible. This was the only time in recorded history that a member of a non-literate people independently created an effective writing system. (source wiki)

|

How is meaning possible? What indeed is meaning? Whether we speak Turkish, Danish, Chinese, or Maori, we take for granted that we can express content and that others can grasp it. But what are the mechanisms that lie behind this? What is their structure? What must the world be like if language is to function as a way of communicating information? And - the key question for this course - what, if anything, does logic have to do with any of this? This course attempts to provide some answers, and it attempts to do so in two ways. First, it attempts to indicate some interesting topics to think about: the big three topics in this course are the notion of event and the inferential role it plays, the ideas of Discourse Representation Theory (DRT) and the anaphoric account of presupposition that they give rise to, and the notion of perspective taking over multiverses of worlds, times and epistemic states. But secondly, and perhaps more importantly, I will attempt to present a systematic account of the role of logic in the study of meaning. Much of the course discusses semantics, or literal meaning. But that is only a part - and perhaps not the most important part - of what meaning is. So I will also say something about pragmatics, or how meaning arises when we actually use language. And, needless to say, I will try to explain what logic has to do with pragmatic meaning. The distinction between reasoning from a representation and reasoning towards a representation is a theme that will recur throughout the course. The course is introductory. It is not intended for experts, but for novices, and I will not presuppose any prior knowledge of linguistics. But in order to give even a superficial overview of the topics just sketched, I will have to assume that attendees have at least a basic familiarity with propositional and first-order logic. That is, I will assume that I can write down basic expressions involving first-order quantifiers and the familiar sentential connectives and expect course participants to read and understand them. |

lecture list

background reading

|

Representation and Inference for Natural Language: A First Course in Computational Semantics by Patrick Blackburn and Johan Bos Paperback: 376 pages Publisher: Center for the Study of Language and Information (April 6, 2005) Language: English ISBN-10: 1575864967 ISBN-13: 978-1575864969 Parts of these lectures trace back to this book, and it gives some useful background for topics merely hinted at in these lectures. It teaches semantic construction using the lambda calculus, discusses how to cope with quantifier scope ambiguities, and shows how to use first-order inference tools to reason to, and from, representations. |

|

From Discourse to Logic: Introduction to Modeltheoretic Semantics of Natural Language, Formal Logic and Discourse Representation Theory

by Hans Kamp and Uwe Reyle Paperback: 717 pages Publisher: Springer; 1993 edition (July 31, 1993) Language: English ISBN-10: 0792310284 ISBN-13: 978-0792310280 A detailed introduction to Discourse Representation Theory, one of the most best known semantic formalisms. As it name suggests, it is intended to handle extended discourses, not merely single sentences. It covers an impressively wide number of phenomena including temporal representations and plurality in a natural fashion. |